Today we had a breakfast van operating in our layby, so Warren had a bacon and egg roll for breakfast! Then, on to McDonald's for a little computer time, and then back to Bletchley Park.

Today we were going to get into the automated side of code-breaking. For the Enigma machines, once Hut 6 had given you a set of plug-board settings, all that you had to do is to type the code into an Enigma machine, with all possible rotor settings, until plain (German) text came out. Simple! You only had to try 150,000,000,000,000 combinations! This is where the Bombe came in. For a start, each Bombe could be pre-set with 'best guesses' as to the first plugboard setting. This reduced the total run significantly. For a second point, once the first rotor setting had been confirmed, it was fairly trivial for an operator to run the coded message on a tester machine — effectively, a single enigma machine, to find the second and third rotor settings, and thus the full Enigma setting. Each bombe could emulate simultaneously 36 Enigma machines, and could run the whole coded text through each one in less than a second. Add to this that there were about 200 Bombes functioning, some at Bletchley, some in London — the Americans had even built their own version. Typically, they got the settings for an entire German Enigma network (there were quite a few) within 2 or 3 hours. The codebreakers prioritised the networks that were most tactically sensitive, and so had most of the major networks wide open for decoding for most of each day!

The fact that the codes were being deciphered so regularly meant that a huge cover-up had to be instituted, which was an integral part of 'Ultra'. Wherever possible, an alternative explanation for the Allies having the information was fed to the Germans. Typically, evidence that a spy had reported the information was 'provided' to the Germans in as convincing a way as possible. The allies had to resist acting upon all the information received, or the whole story would be blown.

We found out later that it has only recently been determined that the story of the British High Command not warning Coventry of an imminent and devastating air raid that effectively levelled the city was just that — a story. In reality, by the time the Enigma messages had been intercepted, decoded, passed to the High Command, the bombers would have already been well over Coventry! In fact, on the high seas, they did blow the deal by sinking one too many supply submarines. The Germans, suspicious, added an extra rotor to their naval Enigma machines, and the resultant 10-month blackout of decoding cost the allies a significant amount of shipping.

But Enigma — and the Bombe — are just part of the story.

The Germans had another coding device, reserved for top-level communication only. This was the Lorenz Machine. It was big, cumbersome attachment for a standard teletype — but supposedly unbreakable. Where Enigma had 150,000,000,000,000 possible settings, Lorenz had 12 rotors and 1.6 million billion start positions — a daunting prospect.

But one of the code-breakers, Bill Tutte, went away and worked out in about 2 weeks the physical structure of Lorenz. Still, the number of combinations that would have to be tried was huge. Here is where John Tiltman came in. He noticed one Lorenz message sent twice (because the first sending had not been received properly), and the sender, against all procedures, had not bothered to reset the machine between sendings. So he had two messages with the same Lorenz Settings. This would not have helped much, but for the fact that with the long message being sent out twice, the operator abbreviated some of the words — so, for example, 'NUMMER' became 'NR' and so on. This meant that the two messages, even though coded with the same machine settings, were now out of step — just the kind of material for a code-breaker to sink his — or more often her — teeth into.

From July 1942 to July 1943, the figuring out of the Lorenz wheel settings was carried out by hand in the Testery. In June 1943, a rather temperamental machine nicknamed 'Heath Robinson', developed by Max Newman, went on line and did most of the hack work in determining the Lorenz wheel settings until January 1944, but is was slow and unreliable — the input paper tapes, for example, kept on snapping.

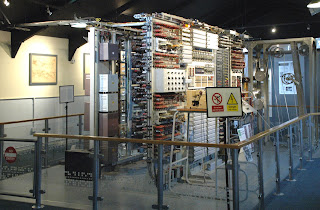

In February 1944, 'Colossus' went on line. This machine, developed by Tommy Flowers, built on the experience of 'Heath Robinson', but also drew on Tommy's long experience as a GPO engineer on the telephone network. Here, although it had no memory storage, was the world's first digital computer —two years before ENIAC, long claimed as the first. It was the Official Secrets Act that prevented Tommy Flowers from getting his due recognition as a computer pioneer — and patents that would have laid the entire fledgling computer industry in British, not American, hands!

The 'Colossus' computers — there were ultimately ten of them (the current rebuild Colossus MkII is housed in Block H, precisely where Colossus No.9 had operated) ran on valve technology (with 2,500 valves!), and they had a paper-tape reading setup that could handle 5,000 characters per second. As they had no memory storage, the text to be deciphered was committed to paper tape, and read and re-read for each iteration of the process!

Anyhow, in The National Museum of Computing Both the Tunny 'Heath Robinson' machine and 'Colossus' have been rebuilt, and can regularly be seen in operation. One of the criticisms Tommy Flowers had to answer was doubt about the reliability of a valve-based machine. His answer was that the telephone system had been using such technology for decades, and was renowned for its reliability. Valves tend to fail with the power surge as they are being turned on and off. The answer to this, during the war, was never to turn the 'Colossus' machines off — they were better off working on code 24 hours per day anyway. With the rebuild, this is not possible, so they have one variation on the original — a power supply that brings the machine on and off line gradually, thus avoiding any surges. As a testament to this reliability, there is one valve in the present 'Colossus' that was manufactured in 1942 and is still going strong!

Have some fun running Colossus yourself on: www.codesandciphers.org.uk — but you will need to be running Internet Explorer, as Tony Sale, the man responsible for the Colossus Rebuild, wrote hos emulators using some code that is Microsoft-specific.

By the way, while we were here, we met Alan Turing's teddy bear!

By the way, while we were here, we met Alan Turing's teddy bear!

Distance driven — today, 23 miles ( 37 km ); to date, 30,843 miles ( 49,637 km )

Great. Heath Robinson machines were impossible structures that looked the part but could not possibly work, was the way i heard that yarn as a kid. I'll leave the colossus to the nerds but the black cylinder is my age!! T ake care and love, cathy

ReplyDeleteI have now caught up the blog and my comments were pithy but thanks for the lot. Love ya, Cathy

ReplyDeleteEnlightening, so thanks.

ReplyDelete